Archives

The Royal Canadian Bicycle Club

Early Sport in Riverdale

by Gerald Whyte

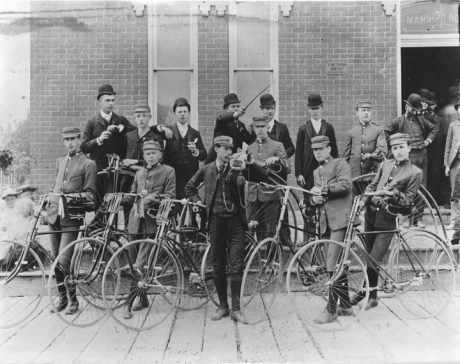

The Royal Canadian Bicycle Club, established in 1891, had its origins in the Royal Canadian Athletic Club, an association of some 100 young men last located at 740 Queen Street East in Toronto. When the new club was formed only five of its members had bicycles and these were the hard tire variety. The first officers of the small club were: David Smith, President, S.H. Gibbons, Captain, E. McTeer, First Lieutenant and Fred Creed, Second Lieutenant. The first home of the club was in the Smith Block at 651 Queen Street East.

Opening of cycling season May 23, 1891, A.E. Walton with the bugle

In the spring of 1892 the club moved to the (Alan Hoover) Dingman Block at 736 Queen Street East where new officers were selected: D. Smith, President, S.H. Gibbons, Vice-President and James Murray, Secretary-Treasurer. in the fall the Club moved to larger quarters in (Archibald) Dingman Hall at 112 Broadview Avenue. Money was a problem for the new club until A.E. Walton, a local entrepreneur and organizer, provided the needed financial management from 1893 - 1896 when he was President. He was to play a major role in Club activities fro 50 years. In the fall of 1903 the Club won its first victory in a team competition at the Cahadian National Exhibition eventually winning a world championship race in 1896.

Cycling in Riverdale received a boost from two dvelopments. The first was external with the invention of the pneumatic tire by John Dunlop in 1888. This allowed a much smoother ride. The second occurred in 1884 when the area of Riverdale north of Queen Street was annexed by the city, allowing for great improvement in local roads. This also allowed a much smoother ride.

The start of the 20 mile Dunlop Trophy Race in 1898

The Dunlop Tire company, as a major supplier of bicycle tires, promoted bicycle racing, an exciting sport, which led to increased bicycle sales. They sponsored their first race at the Woodbine Racetrack in 1894 when the Royal Canadian Bicycle Club competed against four other top club teams. The 20 mile race ended in a dispute which resulted in the Atheneum Club taking the trophy. However the next year the Royal Canadians returned, this time to win. When they won a second straight in 1896 they were allowed to keep the coveted Dunlop Trophy. It is one of the largest trophies in existence, made of ebony and silver and standing seven feet tall! It was valued at $1,000 at the time. The Dunlop Trophy remains to this day at the Royal Canadian Curling Club, the successor club of the bicycle club.

The "east end heroes of the wheel" who won the Dunlop Trophy were: L. Bounsall, C. Leamen, P. Humphreys, H. Parkins, H. Thompson, A. Oake, G. Nicholson, G. Capps, W. Simpson and J. Anderson.

The winning team for the 1899 Dunlop Trophy Race

By 1897 the Royal Canadian Bicycle Club was well established. Their premises in Dingman's Hall are described in the Toronto Evening Star: "The club parlours are upholstered and furnished in the best of style and the pictures of the winning teams decorate the walls. A padded boxing room, a pool room, a card room, a smoking room, a reading room and a first class gymnasium are amoing the attractions."

In 1907 the Royal Canadian Bicycle Club moved into their new clubhouse at 131 Broadview Avenue, J. Francis Brown, architect. in 1929 the name was changed to the Royal Canadian Bicycle and Curling Club when the ice arena was built behind the clubhouse, H.S. Salisbury, architect.

The above is reprinted with the kind permission of Gerald Whyte and the Riverdale Historical Society.

Friday, November 11, 2015

Juno Beach - June 6, 1944 (Photo courtesy of Ian McLean)

Thanks to everyone who keeps the

history and heritage of CCM alive!!

Book Review: Canada Cycle & Motor: The CCM Story

By David Wencer

Canada Cycle & Motor: The CCM Story

By John A. McKenty

Epic Press, 2011

For many generations of Canadians, the letters “CCM” conjure up strong memories, either through the bicycles and sporting equipment made by the company, or through the employment of friends and family.

For many generations of Canadians, the letters “CCM” conjure up strong memories, either through the bicycles and sporting equipment made by the company, or through the employment of friends and family.

John McKenty’s book tells the history of CCM, from its complicated origins during the late nineteenth century bicycle craze, through its forays into automobile manufacturing and hockey equipment, until its ultimate demise in the 1983. At times, CCM was an innovator and an industry leader; in other years, it was a struggling competitor, plagued with labour disputes and a poor reputation. As someone with little personal knowledge of CCM, I found this book to be an engaging profile of the company’s fortunes (and misfortunes), as well as an intriguing look at some of the changes in Canada through the twentieth century. CCM also has a strong Toronto connection, with its manufacturing operations based for many years in the northern end of the Junction, and later on in Weston.

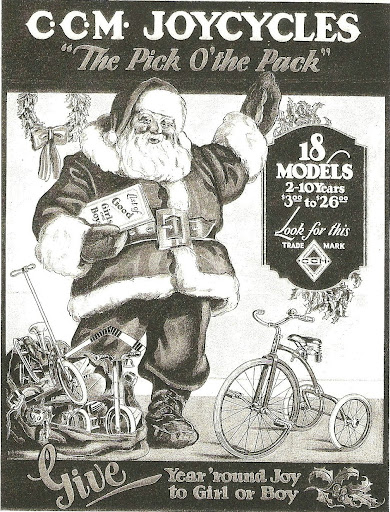

This book features many images, the most interesting of which tend to be the old CCM advertisements. Like McKenty, I have found advertisements to be an excellent means of illustrating a narrative, as one does not have to navigate the copyright issues that can prevent the republication of photographs or newspaper articles. The advertisements are not, however, mere illustrations; in themselves they are valuable parts of Canadiana, and present a side of the company’s story which can be easier for everyday readers to relate to than, say, corporate structure or sales statistics.

That said, this book is not an advertisement for the company. While there is certainly a whiff of nostalgia about parts of it, McKenty is intent on presenting CCM with a sense of balance. I have read histories of other companies which read like protracted, indulgent advertisements, dwelling on the glory years and refusing to say a bad thing about the company or its associated personalities. Sometimes, a company history is written by a nostalgic ex-employee who fills a jumble of casual and irrelevant anecdotes with company jargon and slang, with the end result making little sense to anyone who didn’t work there and know the people being written about. McKenty’s narrative, however, is well-balanced and presents a complicated subject in an engaging and accessible way. Rather than focus on one specific aspect of the company, he gets into the owners, the employees, the products, and the customers, indicating how each influenced the other. The result is an interesting book which looks at several different facets of Canadian history including labour relations, marketing, and popular culture, demonstrating how varied aspects of Canada’s past came together in CCM.

What I found particularly interesting is McKenty’s willingness to point out some of CCM’s villainy. I do not know enough of the facts to know if he is pulling any punches, but there are times in Canada Cycle & Motor: The CCM Story when CCM seems to be severely mismanaged, or when it seems to treat its employees quite shabbily. When the company is managed well, CCM seems to be symbolic of local and national pride; when the quality of products is poor, the company seems like an embarrassment. And when the company is neglected and the employees made to feel the burden, CCM comes across as an enemy.

The book is self-published through Epic Press, which may account for a few of the typographical errors and a handful of awkwardly written passages, although none of these are so major that they really detract from the narrative. I wouldn’t go quite so far as to call these elements “charming,” but they do remind the reader that this book is, like so many books on the history of Toronto, effectively the product of a single, dedicated researcher. And, unlike so many other self-published Toronto history books, there is a sizeable section of endnotes where one can find McKenty’s source material.

While the title and subject matter may suggest an attempt to appeal to those with an interest in business or industrial history, the accessible language and varied subject matter make Canada Cycle & Motor: The CCM Story an interesting look at Canadian popular culture, and indeed a look at a side of Toronto life that doesn’t always get written about. My favourite features are the plentiful advertisements, along with some of the descriptions of cycling culture. This includes not only the late nineteenth century cycling boom, but also a look at some of the racing heroes of the 1930s. If you’re curious about this aspect of the book, I would very much suggest starting with McKenty’s CCM website , in particular the archives section, which includes a look at type of stories which appear in the book. He hasn’t given everything away on the website, and of course the book’s real strength is tying all these anecdotes into a complex narrative.

The above is printed with the kind permission of David Wencer and taken from his website – This Strange Eventful History (http://davidwencer.wordpress.com/)

Mississippi Mills Vintage Bicycle Show: Saturday, June 25, Almonte Community Centre, 182 Bridge St., Almonte, Ontario.

Mississippi Mills Community Bicycle Movement will partner with Causeway’s two cycling social enterprises, Cycle Salvation and Right Bike, to present the 1st Mississippi Mills Vintage Bicycle Show, an exhibition featuring replica bikes from the Canadian Museum of Science and Technology and artifacts on loan from private collectors from across the region. Bicycles on display will range from those pre-dating the Penny-Farthing to classic Italian ten-speeds of the 1990s.

Why not take this opportunity to share your own collection, meet with other collectors from the National Capital area, participate in a bike-part swap, and enjoy a screening of Marinoni: Fire in the Frame, a film about the Montreal-based frame builder and bike racer, Giuseppe Marinoni. Director Tony Girardin will be on hand for a Q&A. Owners of Marinoni bikes are strongly encouraged to exhibit!

If you would like to become an exhibitor or find out more details, please contact Jenny McMaster atjmcmaster@causwayworkcentre.org

2016

CANADIAN VINTAGE BICYCLE SHOW

WINTER SWAP MEET

SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 20

Pleasant Valley Church

100 Market St. South

(just south of the casino)

Brantford, Ontario

7 am – 4 pm

Admission $5 ($10 for vendors)

For further info contact Jamie

Happy New Year to all CCM Vintage folks out there. I have decided albeit a little late to have the CVBS Winter Show & Swap here in Brantford on Saturday February 20/16, as a place to show a few bikes, sell some bike treasures and have a visit with other collectors and like-minded people, a low key fun day to help us through this relatively tame winter we are having this year. The venue is the same location as always 100 Market St SOUTH JUST south FROM THE CHARITY CASINO. It will be from 7am-4pm.The site is under new ownership and is being converted to a banquet hall from the previous church. This year we will utilise the front glassed in showroom for the event. Please bring any tables & chairs that you can and I will see if I can also locate a few. Great chance to maybe find that part you need or the one you have been looking for. Admission is 5$ general and 10$ for vendors or whatever you can afford to donate to the Stedman Community Hospice here in Brantford. Thanks for your continued Support each year. The 2016 15th Annual CVBS & Swap is back again at Heritage View Farm by popular demand on Sunday June 26/16. Start to Spread the Good Word out there on both events and I look forward to seeing many old and new faces alike, bring a friend or two, new blood is always welcome, any questions please let me know.

Best Regards,

Jamie

In April 2004 Massachusetts-based running shoe giant Reebok International Ltd. agreed to pay $204 million in cash and assume $125 million in debt in a deal to acquire The Hockey Company, the company which had evolved from the sporting goods division of CCM. In the year prior to the deal, The Hockey Company had reported revenues of $239.9 million and sales in 45 countries. The acquisition was meant to complement Reebok’s successful apparel business which supplied uniforms for the National Football League and the National Basketball Association. It also enabled Reebok to double the market share of its nearest competitor Nike and its Bauer subsidiary.

In 2005 the newly-formed Reebok-CCM Hockey Inc., the world's largest designer, manufacturer and marketer of hockey equipment, launched its new line of Rbk hockey equipment and sticks. To ensure the line gained instant market credibility, the company signed an up-and-coming young star by the name of Sidney Crosby to endorse it.

That same year the company built a massive head office (the size of ten football fields) in Montreal where they employed about 420 of the company's total global staff of nearly 960 workers. The $20-million facility housed a research and design centre, a laboratory, an on-ice field-testing program, product management and development services, a worldwide distribution centre, as well as a marketing department. The centre was also home to a specially-made robot designed to test hockey sticks and a mini cannon that fired pucks at helmets to check their strength.

The new facility in Montreal was to be operated in conjunction with the company's already existing production plants, including that in St. Jean, Quebec, where 120 people were employed making skates and various pieces of hockey equipment, the Cowansville plant where 90 employees produced Rbk and CCM branded hockey sticks and the Saint-Hyacinthe facility where 140 people produced the jerseys worn ny all 30 NHL teams. Meanwhile helmets were made in Edmundston, N.B. where 60 workers were employed. In Europe facilities were located in Finland where 100 people were employed and in Sweden where an additional 116 people were involved in the manufacture of hovkey equipment under the CCM, Jofa and Koho brands. Additional sales offices were located in Toronto and Germany.

In August 2005, it was announced that the Adidas Group of Germany had bought Reebok International for $3.8 billion. Meanwhile the recently launched Reebok-CCM hockey line continued to be endorsed by NHL stars such as Patrick Roy and Martin Brodeur, while the company remained the exclusive licensee of uniforms for the NHL, the Canadian and American hockey leagues, national teams around the world and several National Collegiate Athletic Association teams south of the border.

Despite its size, the picture was far from rosey for the company. In March 2008, Reebok-CCM Hockey Inc. announced it was phasing out its stick-making facility in Cowansville, Que., and transferring production to its plant in St. Jean. It was a move that meant 90 layoffs and had been necessitated, according to the company, by a serious drop in the demand for wooden hockey sticks. The stick-making operation from Drummondville, Que., had already been moved to the St. Jean facility during Christmas of 2002.

"Indeed, players, whether amateur or professional, now overwhelmingly prefer one-piece composite sticks for their lightness and responsiveness, which has resulted in an approximately 30-per-cent decline in demand for wood sticks in North America since 2004," said Dany Paradis, vice-president of human resources and continuous improvement at the time. (Montreal Gazette, Feb. 9, 2008)

At the same time the Adidas Group announced that 83% of its total apparel volume was now being sourced from Asia, with another 12% from Europe. North America accounted for only 5% and most of that came from Canton Massachusetts.

By now 75% of the company’s hockey equipment was also being sourced from Asia. In 2010 after four years of making hockey helmets and plastic components in the Maritimes, the company closed its operation in Edmundston, New Brunswick, abolishing 40 jobs.

Then in November 2011 came the worse news yet for the company's North American workers. It was announced that 85 of the 120 employees at the St. Jean plant would be losing their jobs because of the continued outsourcing of production to Asia.

"Our competitors all manufacture their products in Asia,” said René Habel, vice president of operations Reebok CCM Hockey. “This is what led us to consider the transfer of our activities in countries where costs are lower."

For the workers it was an all too familiar refrain. Although Reebok-CCM tried to indicate its long term commitment to stay in Quebec, the writing was both on the wall.

Another strategic priority for Reebok-CCM Hockey is to continue to pursue a movement away from own manufacturing to sourcing goods. In 2011, for example, the transfer of helmet production from North America to China was finalised, and the transfer of high-end skates production from Canada to Thailand in 2012 was also announced. Manufacturing activities will be maintained mainly to develop and manufacture performance products for pro level athletes.

(Adidas Group 2011 Annual Report)

Although Reebok-CCM Hockey is currently working hard to capitalize on the legendary history of the CCM name, it is a bittersweet turn of events, for the fact remains that in Canada the brand now exists in name only. Nothing that carries the familiar three letters is made anywhere in the country.