The Evans & Dodge Bicycle 1896 - 1900

With recent interest on here in the E. & D. bicycle and Dave Brown's photos of his great-looking bike, I thought I'd post the following. Although the Dodge brothers were to become the best-known members of the Evans & Dodge partnership, in the beginning it was actually Frederick Samuel Evans (1857 - 1922) who was the key figure in the company.

Born in Hamilton, Ontario, at the age of 18 Frederick Evans went to work as a telegrapher for the Grand Trunk Railway. By the late 1800s he had arrived in Windsor where he established the Dominion Typograph Company (later known as the Canadian Typograph Company). When he and his company were eventually left out of CCM's purchase of the National Cycle & Automobile Co. in 1900, Evans immediately took CCM and its directors to court. By this time, however, the Dodge boys, who had come to Canada in 1892 to work at Evans' typograph plant, were long gone.

Walter G. Griffiths, who was an apprentice at the Typograph plant in 1890 – 1895, recalled the arrival of John and Horace Dodge at the plant. The company had placed an advertisement in the Detroit News for “an assembly man, a floor man.” The Dodge brothers came to the plant to see the superintendent, Mr. Piper, looking for work for both. Piper said he wanted only one man, to which John Dodge replied, “We’re brothers and we always work together; if you haven’t got room for two of us, neither of us will start. That’s that!” Piper agreed to hire the pair and told them to report the next Monday. Griffith recalled that John was the more aggressive and hardworking of the two brothers. Horace still went by the name of “Ed.” Both drank heavily on weekends at various taverns in Detroit, but seldom got into fights because they usually drank with each other, apart from others. (The Dodge Brothers: The Men, The Motor Cars, And The Legacy by Charles K. Hyde)

Walter G. Griffiths, who was an apprentice at the Typograph plant in 1890 – 1895, recalled the arrival of John and Horace Dodge at the plant. The company had placed an advertisement in the Detroit News for “an assembly man, a floor man.” The Dodge brothers came to the plant to see the superintendent, Mr. Piper, looking for work for both. Piper said he wanted only one man, to which John Dodge replied, “We’re brothers and we always work together; if you haven’t got room for two of us, neither of us will start. That’s that!” Piper agreed to hire the pair and told them to report the next Monday. Griffith recalled that John was the more aggressive and hardworking of the two brothers. Horace still went by the name of “Ed.” Both drank heavily on weekends at various taverns in Detroit, but seldom got into fights because they usually drank with each other, apart from others. (The Dodge Brothers: The Men, The Motor Cars, And The Legacy by Charles K. Hyde)

John Dodge's E. & D. Bicycle which now resides in the Detroit Historical Museum.

It was while working as a machinist at the typograph plant that Horace Dodge invented a bicycle bearing that incorporated an enclosed mechanism by which the bicycle rode on four sets of ball bearings. The adjustable four point ball bearing was not only dirt-resistant, but was said to offer a smoother ride with less effort. Horace and his brother John were granted a patent for the bearing in September of 1896.

It was while working as a machinist at the typograph plant that Horace Dodge invented a bicycle bearing that incorporated an enclosed mechanism by which the bicycle rode on four sets of ball bearings. The adjustable four point ball bearing was not only dirt-resistant, but was said to offer a smoother ride with less effort. Horace and his brother John were granted a patent for the bearing in September of 1896.

Shortly thereafter the brothers entered into a partnership with Evans and the trio used a space in the Canadian Typograph plant to manufacture a bicycle using the patented bearing. Known as the “E. & D.” or “Maple Leaf” bicycle, it quickly became a popular model.

In February 1897 Evans displayed the bicycle at the New York Cycle Show and reportedly sold 50 “wheels” to dealers in Philadelphia and New York. In January of 1898, the Canadian Typograph Co. announced plans to open branch offices and retail outlets in London, Ontario and Montreal.

The company also offered bicycle-riding lessons at the Windsor Curling Club. Instruction was free for E. & D. owners and cost $2.00 for five sessions for all others. Separate sessions were offered for the ladies in the morning and mixed sessions for the rest of the day.

In September 1899 when it was announced that five Canadian bicycle companies were to be merged to form CCM, Frederick Evans was irate that his E. & D. bicycle company had not been included. Shortly thereafter (October 1899), he announced the establishment of a Canadian branch plant of the American Bicycle Co., a huge conglomerate of 42 American bicycle makers put together by Colonel A. Pope, maker of the Columbia bicycle, and sporting goods magnate A. G. Spalding.

The Canadian subsidiary of the American Bicycle Co. was to be under Evans' direction and was to be known as the National Cycle & Automobile Co. ("National"). The new company was to include not only the various brands of the American Bicycle Co., but also the E. & D. bicycle and Locomobile motor car.

Evans informed the Canadian public that the bicycle trade previously done in Canada by the companies that were part of the American Bicycle Co. would now be carried on “by a syndicate of Canadian capitalists, who have purchased for Canada from the American Bicycle Co. all their patents, rights, and good-will and business, and will immediately establish in Canada a complete manufacturing plant, capable of turning out not less than 30,000 bicycles per year.” ("Another Great Bicycle Company", Daily Mail & Empire, October 30, 1899)

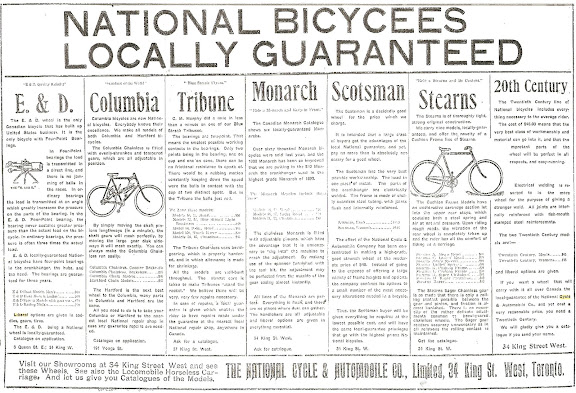

This shows the various brands carried by National.

You know the chances are slim a company will survive when they mis-spell "bicycle."

Among National's directors were A.G. Spalding (New York), Colonel Pope (Hartford), Edward Stearns (Syracuse) and A.R. Creelman (Toronto). At the time the New York Times reported: “The new company is a branch of the American Bicycle trust, but the Toronto business is largely financed in Canada and will be run chiefly by Canadians.” (New York Times, November 20, 1899)

((

While the company was initially to be located in Toronto, it landed in Hamilton when the Toronto Parks and Garden Committee was slow in finding them a suitable location. The Hamilton deal was set out in an agreement between the bicycle company and the city that called for the city to provide an estimated $20,000 for the construction of a new factory, while the company, in turn, agreed to provide full-time employment for at least 300 men for 10 years.

Dave Brown's E. & D.

When National took over the manufacture of the E. & D. bicycle, they agreed to continue to pay the Dodge brothers royalties for the use of their bearing and offered them both jobs. While Horace decided to remain at the Canadian Typograph plant in Windsor, John headed to Hamilton where he was to be National’s general manager. With anticipation in Hamilton running high, temporary facilities were found for the new firm on Barton Street and John Dodge arrived shortly thereafter to oversee the installation of equipment.

From the outset, National made a conscious effort to bridge its homeland with its new home. The company crest featured a prominent British lion and an American eagle hovering under a Red ensign with the Stars and Stripes in the background and a banner that read, “The greatest tandem team on earth.”

From the outset, National made a conscious effort to bridge its homeland with its new home. The company crest featured a prominent British lion and an American eagle hovering under a Red ensign with the Stars and Stripes in the background and a banner that read, “The greatest tandem team on earth.”

Meanwhile Frederick Evans tried to soothe away any suspicions Canadians had at the time that National was a backdoor entry for the American takeover of Canada’s bicycle industry. He pointed out that National was not taking business away from any Canadian concern, particularly CCM, since CCM had never controlled the trade of the firms acquired by National.

In fact, pointed out Evans, CCM would be strengthened “by the effectual shutting out of the possibility of competition by unreliable firms, which might make Canada their dumping ground.” The arrival of National in Canada would, according to Evans, “create a healthy competition which will regulate prices in the interests of the purchasers.” ("Another Great Bicycle Company", Daily Mail & Empire, October 30, 1899)

As it turned out, National's stay in Canada was a short one. In November 1900 it was announced that “after prolonged and well considered negotiations,” Canada Cycle & Motor had acquired control of the National Cycle & Motor Co. and all of its Canadian assets.

As part of the takeover, John and Horace Dodge sold their interest in National to CCM for $7,500 and returned to Detroit where they used the money to open a machine shop, eventually becoming famous for the development of the car that would bear their name.

The only brand-name retained by CCM following its take-over of National was Columbia. As a result when Frederick Evans discovered that neither he nor his E. & D. bicycle was to be included in CCM's purchase of National, he immediately launched what was to be a messy and long-running lawsuit against George Cox and the other CCM directors. With the lawsuit taking several months of arguing and legal wrangling, Evans followed the Dodge brothers to Detroit where he helped establish the Commercial Motor Vehicle Co ., a maker of electric runabouts.

IIn the end, Evans' lawsuit against CCM proved to be unsuccessful thus bringing to an end production of the E.& D. bicycle.