George Henry Parsons (1914 - 1998)

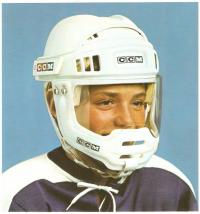

By the beginning of 1976 CCM had developed a hockey helmet complete with eye and face shield and lower face protector that was both approved by the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) and endorsed by the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA). So confident was the company in the helmet's capabilities that it offered free medical insurance to any player who suffered damage to their eyes or teeth while using the helmet and taking part in any supervised game or practice anywhere in Canada or the United States. The helmet and the offer had been inspired by CCM's vice-president in charge of product development George Parsons. Parsons knew only too well the importance of both.

Almost from the time he arrived on the face of the earth, it seemed George Henry Parsons was headed to the National Hockey League. Born in 1914 Parsons was just a young lad when his father contracted equine encephalitis, a debilitating disease that left his dad severely incapacitated, both physically and mentally.

To take his mind off things the young Parsons took to the ice. "The little boy would walk down to a frozen pond at the corner, where he had to keep his sneakers on to fit into his brothers skates. Then he would simply go and skate in circles, faster and faster, until finally they'd send someone in the night to find him." (Sean Kirst, "The Crunch: Understanding Syracuse," The Post-Standard, 03/13/2008)

Seldom was the young Parsons seen without a pair of skates laced to his feet. When everyone else was sledding down the icy slopes of Toronto's High Park on their toboggans, George Parsons was flying down on his CCM Nemos. With his father laid up times were tough for the Parsons' family and by the age of fourteen George Parsons had left school to pour crushed stone and play hockey.

Although the seventeen-year-old Parsons would be invited to the Leaf training camp in 1931, he would play the next three years in the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) Jr. A league, leading the West Toronto Nationals to the Memorial Cup tournament in 1933/34 and the Toronto Young Rangers there in 1934/35. In 1935, as a member of the OHA Toronto "Senior A" All-Stars, Parsons led the team to the Allan Cup tournament, before signing with the Maple Leafs in October of that year.

Known for his graceful skating and crisp passes, it was Parsons' blistering shot that earned him the nickname of "Thunderball." According to Parsons his shot had been developed by placing a couple of boards at the back of a shed and then tapping nails into the outside board. Parsons maintained he would then drive the nails in the rest of the way into the board by shooting hockey pucks at them, a skill that took considerable power and accuracy.

Parsons would spend the 35/36 and 36/37 seasons with the Syracuse Stars leading the team to the Calder Cup, designated for the champions of the newly-formed American Hockey League, in the 36/37 season. That season the 22 year-old Parsons joined the Toronto Maple Leafs late in the season for the play-offs before making the leap full-time the following year.

Parsons' hockey career would come to a sudden end, however, on March 4, 1939, in a game against the Chicago Black Hawks when the blade of Earl Robertson's stick clipped him in the eye.

"He got his stick under my arm and was just trying to lift it to get the puck," recounted Parsons. The end of the stick hit Parsons in the left eye and cut his retina causing him to lose sight in the eye and forcing hime to eventually have it removed.

"They called specialists from Chicago and New York, but they said they had never repaired anything bigger than a pin head. This was half an inch. If it happened today, I might have been back in two weeks, but they just didn't have the equipment in those days," Parsons would later recall.

Parsons applied to the National Hockey League for permission to keep playing, but was turned down.

"League president Frank Calder told me that I couldn't play in the NHL again," said Parsons who was twenty-five at the time of his forced retirement. "Calder said the NHL governors wouldn't allow one-eyed players in the league because of the Trushinski precedent. Calder said the NHL didn't want that happening again."

The Trushinski Bylaw had been so-named after Frank "Snoozer" Trushinski a minor leaguer who had played defence for the Kitchener Green Shirts. According to NHL officials at the time Trushinski had lost his sight in one eye due to a high stick in 1921. He returned to play again and lost most of the sight in his other eye after sustaining a skull fracture in another hockey mishap. Not wanting to expose its players to further injury and wishing to avoid the increased cost of the insurance, the National Hockey League created Bylaw 12:6 prohibiting players with reduced sight from playing in the NHL.

While the Leafs looked after Parson's medical and hospital bills and paid his salary for that full season, the league agreed to use a contingency fund established in 1938 to ensure that Parsons received a weekly salary of $40. The assistance was to continue until such time as his salary reached that amount.

And so it was that in May of 1939 company president George Braden hired Parsons to work in the paymaster's department at CCM. The dedicated Parsons would lose no time in moving up the company ranks to become CCM's North American sales manager and eventually its vice-president in charge of product development.

Over the years his role at CCM allowed Parsons to maintain a close relationship with the Maple Leafs, enjoying each home game from his rail seat, as well as a number of prominent hockey stars including Bobby Hull and the Bruins Derek Sanderson who when the 10-speed craze hit in the early 70s reminded Parsons that there were over 600,000 college students in the greater Boston area. "George if you can get the bikes...ten speeds remember...I think we'd have a good thing in Boston," maintained the flamboyant Sanderson. (Toronto Star 04/06/71)

While Parsons would oversee the development of many pieces of equipment in his close to forty years with CCM, none would give him as much satisfaction as the evolution of the CCM hockey helmet.

For years Parsons had lobbied publicly to have the wearing of a helmet mandatory in minor hockey. His efforts, and those of like-minded individuals, would come to fruition in 1976 when the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) declared that all its players would be required to wear CSA-certified helmets.

It was following the release in June 1975 of the report of a committee formed by the Canadian Opthalmalogists Association to study the incidence, types and causes of eye injuries in hockey that officials at CCM announced the launch of the company's full face guard and corresponding insurance policy.

"Now we are happy to say that we are so confident our equipment is safe that we are willing to extend this kind of guarantee," reported CCM president Graham Eaves. "An insurance policy which we unofficially call the 'Parsons Policy" .....to all those wearing the CCM helmet, eye shield and lower face protector."

Parsons' efforts were further validated in August 1978 when NHL president John Ziegler announced that protective headgear was to be worn by all players in the National Hockey League.

Despite having his hockey career cut short, George Henry Parsons had made a considerable contribution to the game he loved, so much so that in 1973 CCM and the OHA recognized that fact by instituting the George Parsons Trophy to be awarded annually to the player judged to best combine ability and sportsmanship at the Memorial Cup tournament. It remains a wonderful reminder of what one can accomplish despite suffering a physical setback.