Miller on a roll with antique bicycles

by

Beverley Ware

MERSEY POINT — It’s not that Ron Miller has an obsession. It’s more like an extremely enthusiastic passion.

Admittedly, it’s hard to miss the penny farthing in his living room. Or the full-sized antique wooden bike on a shelf high up on his living room wall. Or the bike frame hanging from the ceiling.

Miller loves bicycles. He has large bikes, small bikes, bike lamps, bike chains, bike pedals, bike horns and even bike bugles.

Where most people would have a dining room cabinet display of crystal or china, Miller has dust-free bike lights and horns and cyclometers, which would measure how far the cyclist had gone.

There’s no media room in the finished basement of his waterfront home in Mersey Point, just minutes outside Liverpool. That, too, is filled with bikes.

Besides being all-things bicycle, there’s one other thing Miller’s treasures have in common: they’re very old.

The penny farthing in his living room, for instance, was made in 1888, and Miller’s thrilled the weather is warming up so he can get outside and ride it. The wooden bike perched high on the wall in the living room was made around 1890.

But Miller’s most treasured piece is an adult tricycle made in 1884 by the British motor company Rover.

“It’s the only one like it in the world, as far as I know,” he said.

Miller biked a lot as a kid. He got his first bike, a green three-speed Raleigh, in 1952 when he was 10 years old, and he rode it everywhere. That is, until he turned 16, when he sold it and bought a Volkswagen car.

While he owned several cars over the years, the spirit of that bike never left Miller. When he was 30, he tracked it down and bought it back.

“It was just sentimental,” he recalled with a smile.

Some of the bikes Miller finds in flea markets and at auctions.

“Frequently they find me.”

Such as the Rover. Miller said someone spotted him driving to Halifax one day with the penny farthing on the back of his car. That person phoned a friend in Halifax who happened to know Miller, so the man asked his friend if he thought Miller would be interested in an old tricycle he had at home in Chester. He had no idea how rare the adult bike was.

It seems Miller’s head is filled with as much information about bikes as his house is filled with bike paraphernalia.

The first bikes were made in 1818, he said, and were basically two wooden wheels with a wooden frame — no chain, no pedals — and the cyclist sat on the seat and ran.

Pedals were added to the front wheel in 1865, leading to the development of the penny farthing because a cyclist had to pedal like crazy to make the small wheel get up to any speed.

The penny farthing went out of fashion when the bike chain was introduced because it meant the front wheel didn’t need to be huge anymore.

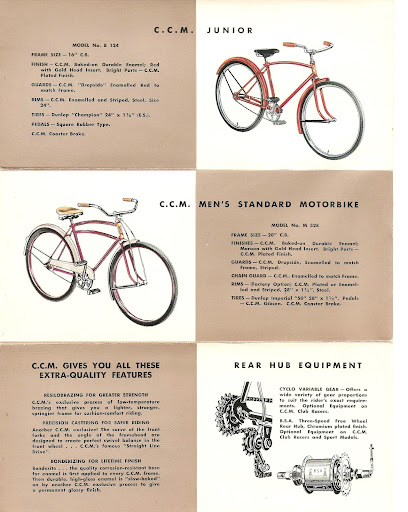

Miller can also tell you about valves on bike tires — the European one is the best because it doesn’t let out air — and that CCM made its first bike in 1899. It almost went out of business that first year but managed to hang on until 1983, when it sold its name to a Montreal company.

Rubber tires replaced wood around 1888 and led to the first real bike boom, but the tires weren’t perfected for years.

“It’s complex to get a simple, reliable, workable tire,” Miller said.

It would be 90 years before the next bike boom hit during the oil crisis of the 1970s.

At 70, Miller doesn’t just admire bikes, he makes tremendous use of them, joining cyclists from around the world each year for trips in England and Europe.

Last year, he cycled from London to Kent, in England. This spring, he’ll ride his 1924 Sunbeam from Prague to some other town in the Czech Republic.

“I think I’ve done the Rhine River three times, its entire length.”

He cycles from 50 to 100 kilometres a day on these trips, averaging about 500 kilometres a week.

A retired mechanical designer with the Ontario Science Centre, Miller has created a little business on the side to meet the unique needs of antique bike lovers around the world, though he concedes he doesn’t make any money at it.

He developed a system to make vacuum-formed rubber pedals to replace damaged antique rubber in old metal pedals.

He puts the original rubber part into a tube, pours liquid silicone rubber inside, then adds polyurethane rubber and seals it. He puts it in a vacuum system that he developed to remove any bubbles, then puts it into his homemade pressurized chamber. After sitting under four tonnes of pressure for eight hours, the new pedals are ready to be mailed to customers around the world.

Miller said the only real change to the bicycle in the past 120 years has been its technology and materials.

That aside, cycling still comes down to one thing.

“You still have to have good strong legs.”