From the hockey files......

A Skate Magician

© John McKenty 2012

Born in 1948, I moved with my family to the village of Portsmouth, Ontario, just shortly after it was annexed by the city of Kingston in 1952. It was a union given little attention by the villagers who went about their daily lives as if they were still a recognizable entity unto themselves.

While Portsmouth had the usual small-town amenities such as a corner store (Beckie's), a drug store (Peter's), a barber shop (Ernie's), a hardware (Baiden’s) and a Red & White (Cowan's), it also had an “insane asylum” (Rockwood), as it was known at the time, two rather rowdy hotels (Lakeview Manor & Portsmouth House), as well as two maximum security prisons, one for the men and one for the women. It also had two schools and two churches, one each for the Catholics and the Protestants. Pretty heady stuff for a community of about 500.

With the hotels and prisons standing as a stark reminder of what can happen when one is led astray, it was around this time that local building contractor Harold Harvey, bothered by the frequent sight of children playing in the streets or just hanging out, founded the Church Athletic League, an organization offering recreational hockey, softball, basketball and bowling for young people. The one stipulation was that all participants must attend church or Sunday School 80% of the time. It was Mr. Harvey’s valiant attempt to set the village's and the rest of the city’s youngsters in the right direction.

When the Church Athletic League began its first season of hockey in 1951, it had 100 boys signed up. As the league continued to grow, however, Harvey came up with a plan for a new outdoor rink to be built at the old quarry in Portsmouth, where 19th-century prisoners had once hammered limestone into building blocks. So it was that the Harold Harvey Arena was constructed in 1960 at 42 Church Street, directly across from where I lived at 35 Church St. Over time, my two brothers and I, as well as our dad, would work at the venerable old arena which would begin life as an open-air affair, before eventually being closed in.

Back in those days everyone in Portsmouth brought their skates to Baiden's Hardware to be sharpened. It was a retail operation overseen by Henry Baiden and his younger brother Bill. The problem, according to many in the village, was that Bill knew how to sharpen skates correctly, but Henry didn’t. As a result, before you took your skates in to be done, you peered cautiously around the corner of the store’s front window to ensure that Henry was busy and Bill was not.

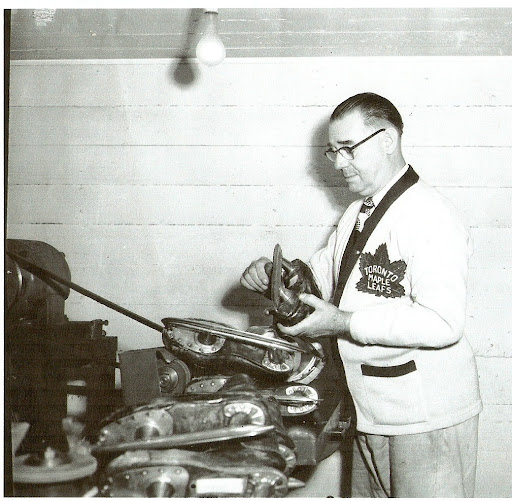

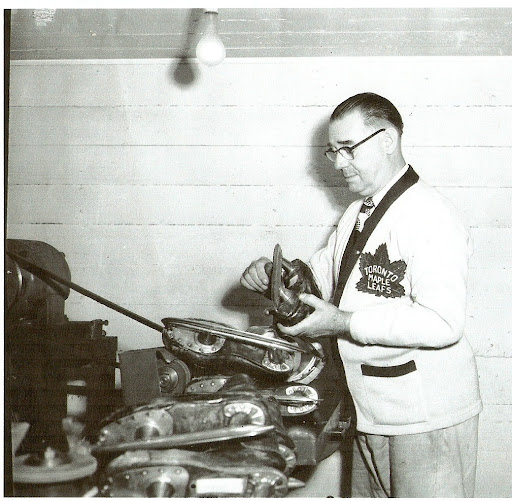

It had long been known that sharpening a skate blade properly was an art form not easily mastered by just anyone, a fact acknowledged by the Toronto Maple Leafs, who for years came to depend upon the team's equipment manager, Tommy Naylor, to keep their blades finely tuned. Naylor’s reputation as a master on the skate machine was such that he would eventually be asked to accompany Team Canada to Europe for the Summit Series in 1972.

It had long been known that sharpening a skate blade properly was an art form not easily mastered by just anyone, a fact acknowledged by the Toronto Maple Leafs, who for years came to depend upon the team's equipment manager, Tommy Naylor, to keep their blades finely tuned. Naylor’s reputation as a master on the skate machine was such that he would eventually be asked to accompany Team Canada to Europe for the Summit Series in 1972.

A summer employee of CCM, Tommy Naylor was born in 1904 and was first employed as a messenger boy for the A.G. Spalding & Bros. Sporting Goods Co. in Toronto. When the regular skate sharpener quit, the company offered the job to Tommy, who, at the time, was also the stick boy for the Toronto Arenas. Tommy took the skate-sharpening job, eventually ending up with the Leafs, where he was variously listed as the team’s assistant trainer or equipment manager.

Among those who praised the way Naylor handled his skates was perennial Leaf all-star King Clancy.

“He never rockered them and I went along with that. Some players liked them that way, but I preferred flat, believing that the more blade you had on the ice, the faster you could go,” said Clancy. (1)

Working in a room under the stairs at the north-east corner of Maple Leaf Gardens, Naylor was sought out by the leading skaters of the day. In 1936 when CCM sent a shipment of skates to Los Angeles for use in her ice show, Sonja Henie, who was notoriously finicky, wanted Naylor to accompany the skates, but he declined.

Henie wasn’t the only famous figure skater to seek out the expertise of Tommy Naylor. Prior to her departure for Europe and world acclaim in 1948, Canada’s sweetheart, Barbara Ann Scott, also paid a visit to Naylor who had been sharpening her skates since she was seven.

Frick and Frack, two comic Swiss skaters, who performed as members of the Ice Follies, seldom appeared in Toronto without looking up Naylor, whom they called the top “skate man” in the world.

George Hayes, a linesman for twenty years in the NHL, recalled visiting Naylor in his skate room where the walls were covered with old photos, hockey calendars and newspaper clippings.

“He always did a fine job and wouldn’t give them to you if they weren’t just right. He always shellacked the toes of your skate boots and if your laces were a little worn, he’d put in a new pair. Then he’d say, ‘Compliments of the Toronto Maple Leafs,’ but we’d always make him take something a smoke or a beer,” recalled Hayes. (2)

Naylor was such an integral part of the Leaf operation that in 1951 when Conn Smythe, owner of the Leafs, looked at the annual team photo he inquired as to why Tommy Naylor wasn’t in the picture. When told that Naylor hadn’t been asked, Smythe bellowed, “Get the team together with him and take another photo!” (3). From then on, Tommy Naylor was in every official Toronto Maple Leaf photo.

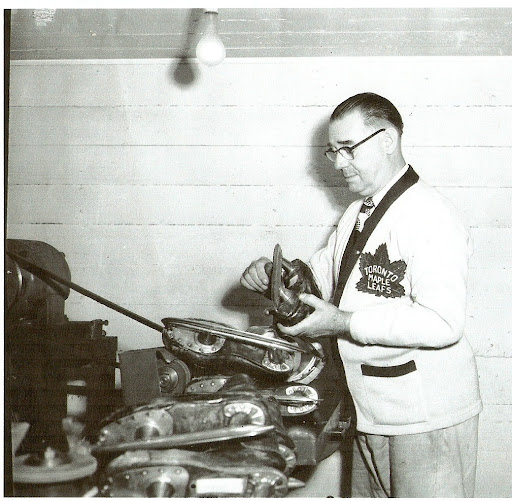

When he wasn’t working on skates Tommy Naylor used his time to try and improve the quality of the equipment being used, including the creation of a trapper glove that goalies could wear. It was following a chance encounter with baseball’s George McQuinn of the Toronto Maple Leafs in the International League that Naylor used the first basemen's glove to come up with a definitive piece of goalie equipment.

“Well I took his old glove and I put a cuff on it and I gave it to Baz Bastien who played goal for the Senior Marlboros.” (4)

The success of the endeavour convinced Naylor to sew a strip of leather in Maple Leaf netminder Turk Broda’s catching glove which up to that time had only had a lace between the thumb and the forefinger. The reworked glove performed so well for Broda that soon goalies throughout the league were looking for one.

When Hap Day of the St. Pats cut his Achilles Tendon in 1926, Naylor used a most unusual item to come up with some protection for the back of Day’s ankles.

“Well I took the stays out of ladies corsets and shaped them down and slid them into nylon pockets, and sewed this into the heel of the hockey boots. These were the first Achilles-tendon guards. I did the same thing on the tongues of Teeder Kennedy’s boots. He was always getting cut on his instep,” explained Naylor. (5)

Naylor used the same principle to add ligament shields to a player’s shin pads and to develop the padded guards most defencemen would end up wearing around their ankles.

Over the years, despite the ongoing upgrade in equipment, the sharp end of a skate blade remained a constant threat to player safety. Prior to the start of the 1959/60 NHL season, CCM announced that Maple Leaf centre Red Kelly would be wearing a new type of guard on the end of his skate blade. Designed by CCM engineer Bill Shaw, it had been developed in consultation with Tommy Naylor.

The need for such a piece had been intensified when Leaf defenceman Allan Stanley fell in a game against the Montreal Canadiens striking his cheek against the back of Bill Hicke’s skate blade. Stanley came away from the encounter with twenty-five stitches and a broken jaw.

Following the game, Canadiens’ coach Toe Blake suggested that a metal guard connecting the end of the blade to the bottom of the boot should be standard on all skates. Naylor wasn’t so sure.

“There’s no guarantee that’ll prevent injuries. It’s much more important to round that part off when the skate is being sharpened,” maintained the soft-spoken Naylor. (6)

So it was that he and Shaw set about designing and refining the plastic tip which would soon be adopted by all the major skate manufacturers.

There were many who held that if the unassuming Naylor had patented all the inventions he had come up with, he’d have retired a millionaire. But Tommy Naylor didn’t do it for the money and nobody knew that better than Vic Hunt.

A goalie with the Toronto Dukes Jr. B Club, Hunt had been just eighteen years old when his hand was crushed by a press machine at the printing plant where he worked. The doctors had no choice but to amputate eventually fitting Vic with a hook for the stub of his right arm. While Conn Smythe offered to make the lad the Maple Leafs’ stick boy so he could stay involved with hockey, Vic Hunt had a different idea, one that needed the talent of Tommy Naylor.

Working with Hunt, over time Naylor rigged up an attachment that he bolted to the handle of the young man's goalie stick. With the attachment fitting into the hook of his right arm, Vic Hunt used a specially-designed hockey glove to cover the apparatus and to fulfill his dream of returning to the ice. Helping dreams come true was what Tommy Naylor did, but he didn’t do it for the money.

(1) King Clancy and Brian McFarlane, Clancy, (Toronto: ECW Press), 1997, p.95

(2) George Hayes. "Naylor Belonged," Daily Sentinel-Review, Feb 18, 1981

(3) ibid.

(4) Trent Frayne, "Our Memories & Foster Hewitt's Voice Made It Toronto's Most Famous Building," Toronto Star, Oct. 3, 1970

(5) ibid.

(6) Jim Proudfoot, "Skate Guards Could Worsen Injury - Naylor," Toronto Star, Dec. 9, 1960